As the Level 4 ‘drought’ continues, and some shallow well owners are concerned about their water supply, CKTZ News asked an expert about Cortes Island aquifers.

Dr Diana Allen is the head of the Groundwater Resources Research Group at Simon Fraser University. While she has not been to Cortes Island, Allen has been working on islands like Hornby, Mayne, Saturna and Salt Spring since 1996.

Will the Cortes Island aquifer collapse?

The most alarming concern is that people drilling wells could punch holes in the island’s aquifer and cause it collapse.

This idea was expressed during an interview last week, during which John Preston also pointed out that what used to a be year round wetland, in Whaletown, has been drying up every summer for the past five years.

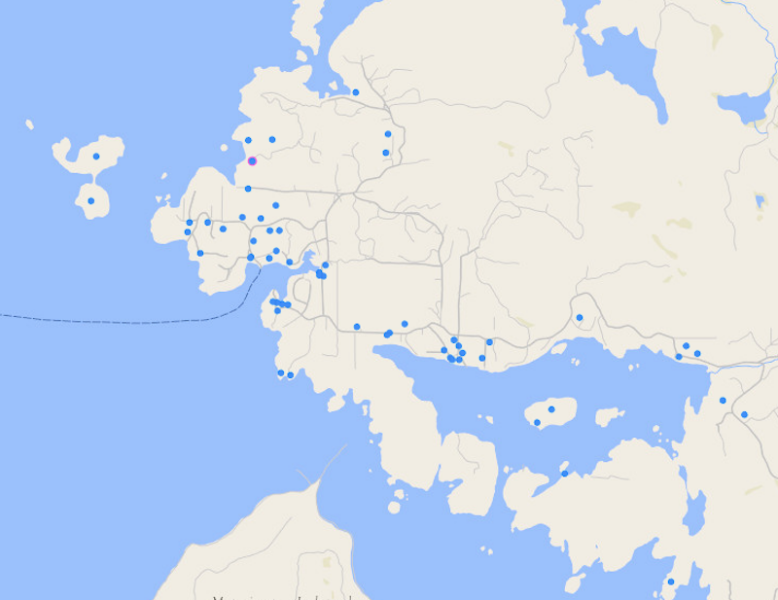

CKTZ news contacted Red Williams, a well driller from Parksville who serves the surrounding area on Vancouver Island, the Sunshine Coast, Quadra and Cortes Islands. While he sometimes hears this fear expressed, Williams said he has never encountered a case of an aquifer collapsing. The main problem he has seen is some shallow wells run out of water during dry spells. He said this is an ongoing problem, but there are ways that homeowners can extend their supply and the aquifer is replenished when the rains come.

“Yes, I agree with him,“ said Allen, adding, “Well, I guess it depends what someone considers to be collapsing an aquifer.”

Allen went on to talk about subsidence, adding that she has heard of it in places like California’s Central Valley and Mexico City, but not British Columbia.

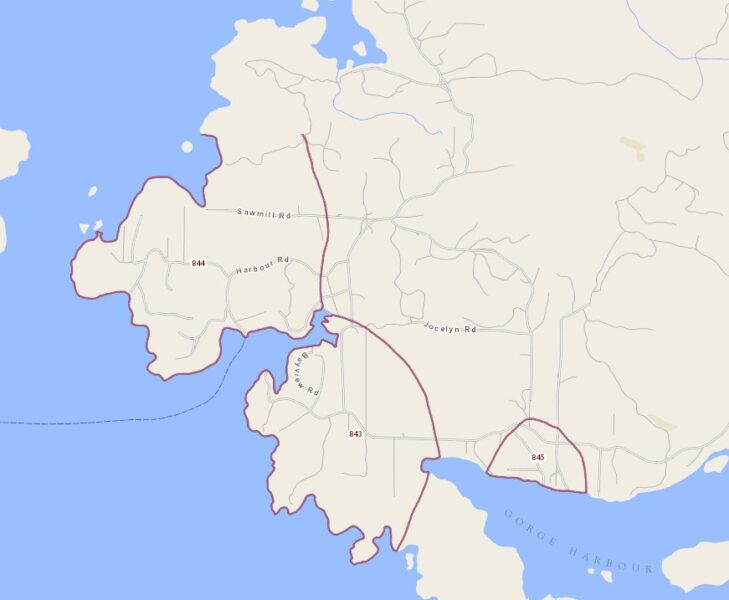

Aquifers 843, 844 & 845 in Whaletown are in bedrock. Screenshot from iMapBC.

Registered wells (since 2007) in Whaletown. Photo courtesy of iMapBC.

The registered aquifers

Allen spoke further about subsidence and aquifers.

“When you take ground water out of an aquifer that consists of interlayers of sand and clay, there is the potential for the clay to lose whatever water it has in it and squish. That can cause subsidence,” Allen explained. “You have to take a lot of water out … huge quantities, or also where oil and gas have been taken out of deep sedimentary rocks … but for small aquifers, like what you would find on Cortes Island, I do not think subsidence would be a real problem.”

Taking CKTZ News on a virtual tour of the Cortes Island aquifers on the iMapBC website, Allen discovered that all three of the aquifers that cover much of Whaletown (#843, #844 & #845) are in bedrock, where subsidence is not an issue.

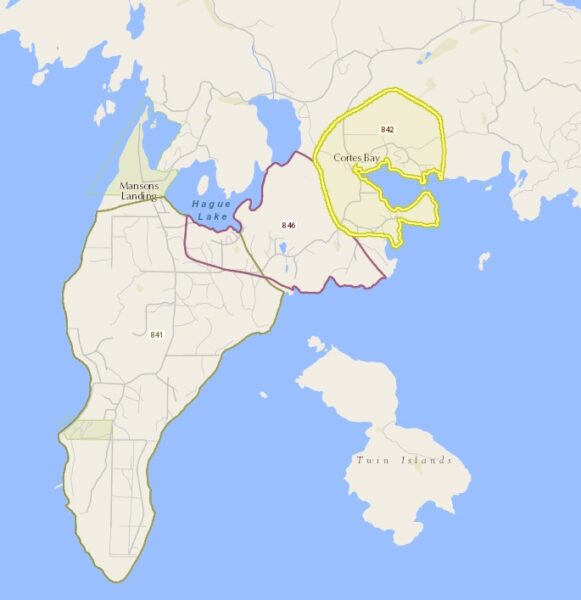

Aquifers 841, 842 and 846 in Mansons Landing. Photo courtesy of iMapBC.

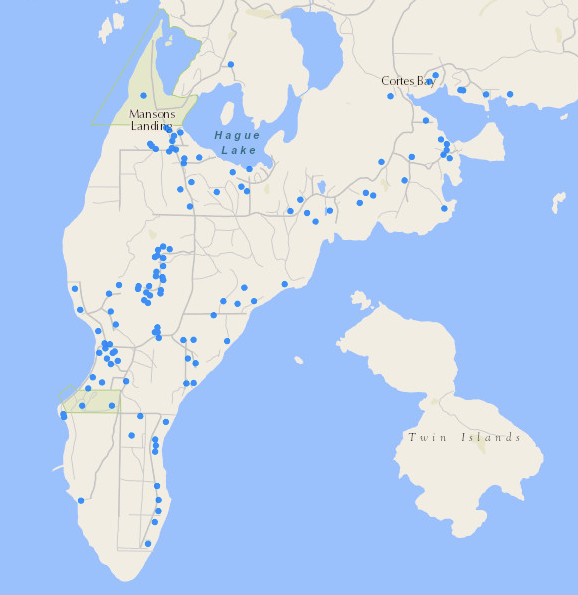

Registered wells (since 2007) in Mansons Landing. Photo courtesy of iMapBC.

Aquifer #841 which feeds most of the land between Mansons Landing and Sutil point, is sand and gravel.

“When the glaciers were all melting, they would have dumped a whole bunch of sand and gravel on this point. This is actually a confined aquifer, so there is some clay over the top of it that is providing natural protection to that aquifer. So this would be a good quality aquifer,” she explained.”

Aquifers #842 and #846, which feed the area between Mansons Landing and Cortes Bay, are in rock.

“So it is really only this southern tip. All the other areas that have been mapped with aquifers show bedrock,” said Allen.

Where aquifers are not mapped

The aquifers feeding more than three quarters of Cortes Island – Tiber Bay, Squirrel Cove and all the lands in the north – are not mapped.

Allen explained that this would have been because this area is so sparsely settled.

Registered wells in Squirrel Cove (since 2007). Photo courtesy of iMapBC.

The 2002 geological survey of Cortes Island map show that most of Squirrel Cove is sand, mud and gravel, but the rest of northern Cortes is primarily rock.

If Cortes Island’s aquifers aren’t collapsing, what explains the wetland, that used to be filled with water year round and has dried up the last few summers?

“That’s where climate change comes in," said Allen.

She had a great deal to say about the salt water that is sometimes found in wells.

Some of it dates to the last Ice Age, when glaciers pushed the islands under the ocean. They remained submerged for 400-500 years, during which time the aquifers were filled with saline water. Rainwater has pushed most of it out, but Allen has found pockets on Salt Spring. She does not know if there is any on Cortes Island, but said it is sometimes found in aquifers that are in rock.

“It is fairly deep down, so most people have their drinking water wells relatively shallow, maybe a hundred metres or so … So they are tapping into water that is replenished on an annual basis, but there is some very deep older water down there that is of Pleistocene/post Pleisticene Age."

Allen did not know if there is still salt water at the bottom of Cortes Island’s aquifers but, especially in more permeable soils, wells sometimes encounter salt water.

“You put a pumping well in and the water from the ocean just says, 'oh, I’ll just go right towards that well.' So any wells that might be nearer to the coast or, if they are in the middle of the island, maybe they are drilled a little bit deeper, there is a natural salt water wedge that underlies all islands,” she explained. “If you drill down deep enough, you will hit salt water. The higher the topography, like Salt Spring, the deeper that sea water is, and the less topography, the shallower. That’s why having a whole bunch of shallow wells is a good thing.”

Allen said that parts of Saturna and Hornby Islands have ongoing problems with salinity. People in the Caribbean do not even drill vertically. They excavate long trenches, skim the fresh water off the top of the aquifer and collect it in cisterns.

One of Cortes Island resident is using rainwater for most of their needs.

“More people should be doing a combination of rainwater collection and groundwater … might as well take advantage of that roof that you have and, if for nothing else, then watering a vegetable garden, flushing toilets, or washing laundry. There are a whole bunch of uses of water that don’t require good quality groundwater,” said Allen.