By Aly Laube

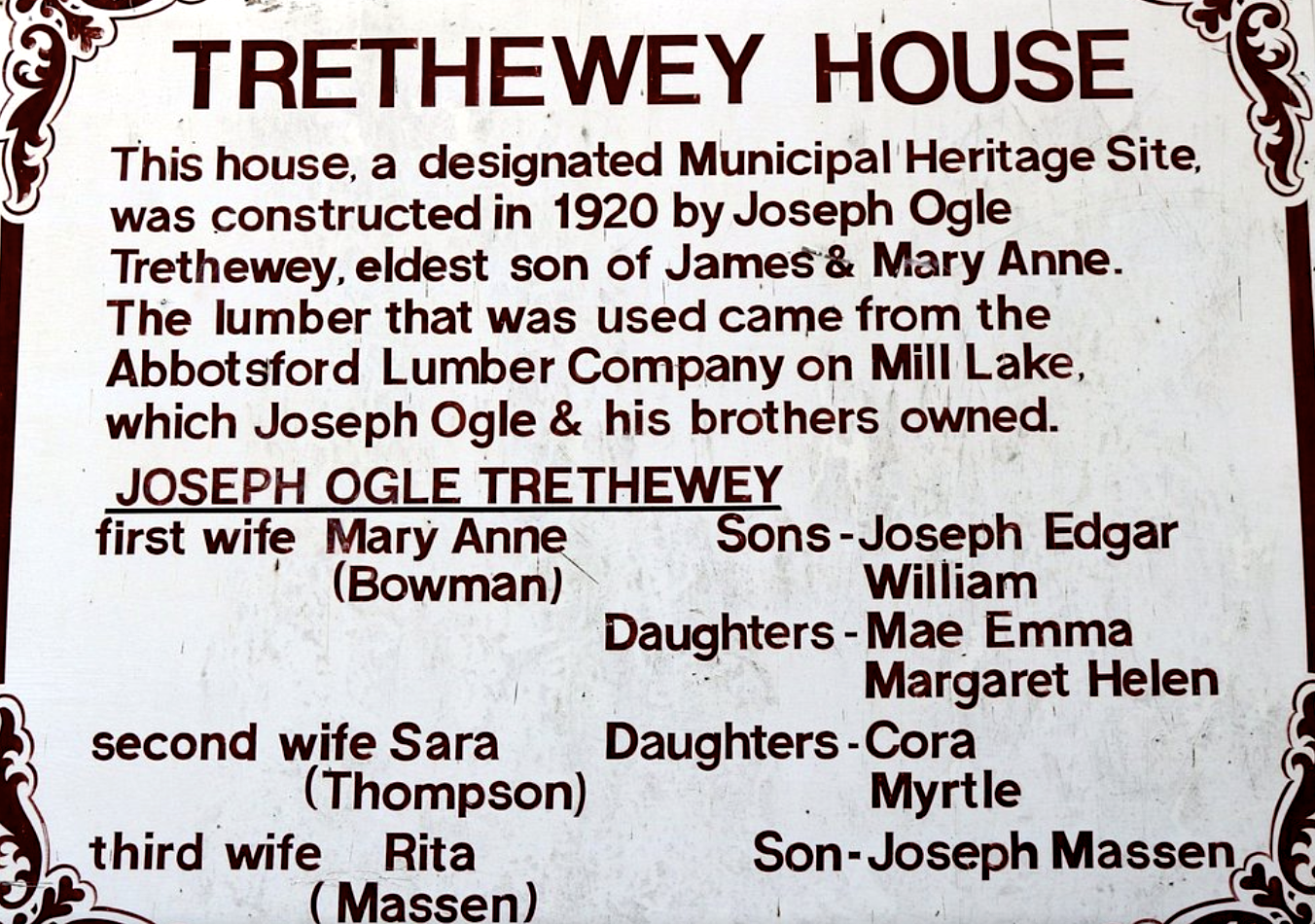

A photo of a sign outside of Trethewey House in Abbotsford, BC.

To understand the nature of systemic racism and white supremacy in Abbotsford, you have to understand the history. But that history can be hard to find, tucked away in archives and couched in vague language. The information is there if you look, and it speaks volumes about the area’s past in relation to upholding structures that support white settlers.

In 1925, American Klu Klux Klan members came to Abbotsford in search of new recruits. For $10 apiece, residents born in Canada, the US, the UK, and Northern Europe who were white, male, able-bodied, Protestant, and “of sound mind” could sign up to join the KKK and become part of an organized effort to “maintain forever White Supremacy.”

“Several notable residents signed up,” reads a statement on the Abbotsford Heritage Society website, which acknowledges that the KKK had “a large following in Vancouver and the Fraser Valley” in the 1920s.

When Olivia Daniels started digging through a digital archive of newspapers, she wasn’t expecting to start a research project on organized white supremacy in Abbotsford. A student researcher at UFV, with a major in history and an extended minor in anthropology, she’s also a student of Ian Rocksborough-Smith, a co-chair of the Race and Anti-Racism Network and professor at UFV.

Daniels discovered the involvement of Dixie Protestant women in Atlanta through one of his classes this summer. That discovery led her to investigate local events organized by groups like the KKK, Native Sons and Daughters, The Odd Fellows, and the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire in Abbotsford over the years. Specifically, she set out to document the festivals and events they held in the city. On multiple occasions, residents were documented wearing costumes based on racist caricatures of people of colour — among them, white people wearing black face and yellow face.

March 1926 was busy for the Abbotsford KKK. They had an overcrowded meeting on March 7, where listeners were told to gather at nightly meetings until the end of the month. There, they could do things like cross burning and night riding under cover of darkness, which they did walking down Essendene Avenue, with hundreds of visitors. She says a majority of the town participated in KKK gatherings, although it’s uncertain if people knew about the after-dark mission and activities of the Klan.

The KKK also made regular efforts to ward off “undesirable immigrant neighbours.” In 1928, there was a series of anti-Roman Catholic lectures at the Orange Hall led by ministers on “the necessity of protestant unity” or “white purity.”

“If you look at the month of March in 1926, it seems to be quite a regular thing,” she says. “They had a lecture, then they had this parade on Essendene, and one of the articles mentions there’s going to be planning for another parade, and another meeting that will occur nightly, they say.”

The Native Sons would hold dances and an annual writing competition based on topics about Canadian nationalism, and the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire also donated large sums of money to local lodges, including the KKK’s Orange Hall. The Brethren of the Fiery Cross and Kilsgaard Kare Klub were two other KKK-affiliated groups that were active in Abbotsford in the 20s.

“You collect money to put in your community, but it’s all based on racism, and a lot of these donations would be meant to hide the more aggressive racism that people would perform. There were two Klan-affiliated groups that I identified so far during the 20s, so that’s the Brethren of the Fiery Cross and the Kilsgaard Kare Klub, which we’ll let go by the KKK,” she says.

“They wanted to take land away from Indigenous people they saw as not being in use,” she says. “Boards of trade were actively lobbying for white labourers only. Most organizations had some level, truly, of white supremacy in them.”

Daniels has a specific interest in the role that women played in white supremacy groups in the 1900s. Although their involvement is largely undocumented, they supported their husbands, fathers, and brothers in their racist and xenophobic actions. Surely they were expected to at the time, but that doesn’t negate the importance of the role of white women in upholding white supremacy.

“They thought as women and daughters of the community that it was their right to speak up, because they had lived through the pioneer life of living in mosquitoes and building their homes and having harsh winters. They felt like they had more of a right to live there than the immigrants,” she says.

In 2019, Heritage Abbotsford released a book called Pioneers and Petticoats about the women of Abbotsford’s pioneering days. This was an initiative spearheaded by Christina Reid, the organization’s executive director, who was trying to include more women in local exhibitions and research. It’s her responsibility to implement its strategic plans, write grants, manage finances, and work with staff.

When Reid and other staff were conducting research for the book, she says people would often ask for true but unflattering details to be kept off the record, meaning they wouldn’t be included in the final product.

Daniels says erasing taboos from history is also part of the problem.

“You don’t talk about mental illness. You don’t talk about things like suicides. You don’t talk about husbands’ philandering, those kinds of things, right? And to me, that’s lying by omission. We don’t talk about things like alcoholism, postpartum depression. These are all things that I believe are omitted from history so that we have this sort of idealized history instead of reality.”

These historical omissions are problematic for people of colour who don’t see themselves reflected in the record. Not only are the contributions of entire groups of people swept from all documentation, their work receiving no thanks, but this false history misinforms generations of Canadians.

Daniels says both the Brethren of the Fiery Cross and the Klu Klux Kare Klub were based around weekly spectacles like parades and public speeches. These were the KKK’s investment into communities they wanted to recruit in, and organizers were profiting off members who paid admission and made donations at their events. She says people in Abbotsford actually paid double or more than they had to at Klan events, showing the support the organization has in the 20s.

Extensive archival records on Abbotsford’s past are stored at Reach Gallery Museum, where Foulds works. She started her career with museums in the 1980s, and part of her job was to search issues of the Abbotsford News for clippings related to the lumber company in local history. Through this studying, she found that racism in Abbotsford was both “endemic” and socially acceptable. For example, she says, there are several groups in the valley that had white-only membership criteria up until the 1990s, such as the Native Sons and Native Daughters.

Canada continues to reckon with its history of racism and oppression. The country's first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, was one of the architects of the residential school system and other colonial policies and structures. MacDonald also spent years trying to ruin, arrest and, eventually, execute Metis leader Louis Riel for not wanting to have his land taken from him.

In recent years, statues of MacDonald have been vandalized, damaged and toppled across the country by activists who say the monuments contribute to a false historical narrative that favours settler culture. It exaggerates achievements and downplays transgressions, or, in this case, the culture's participation in slavery and upholding of white supremacy.

But MacDonald is only one of many historical figures inaccurately represented in the history books. In the next episode, we’re talking about the Tretheweys, one of Abbotsford’s founding pioneer families, who had connections to the KKK. Canada’s history of colonization, genocide and violence towards Indigenous people sets the foundation for the systemic white supremacy that continues to manifest in government today.

This series is by no means an exhaustive list of every incident that has contributed to that history. Instead, it is a reflection led by community experts in relevant areas of expertise, meant to be part of CIVL’s ongoing dedication to anti-racist coverage.