By David P. Ball

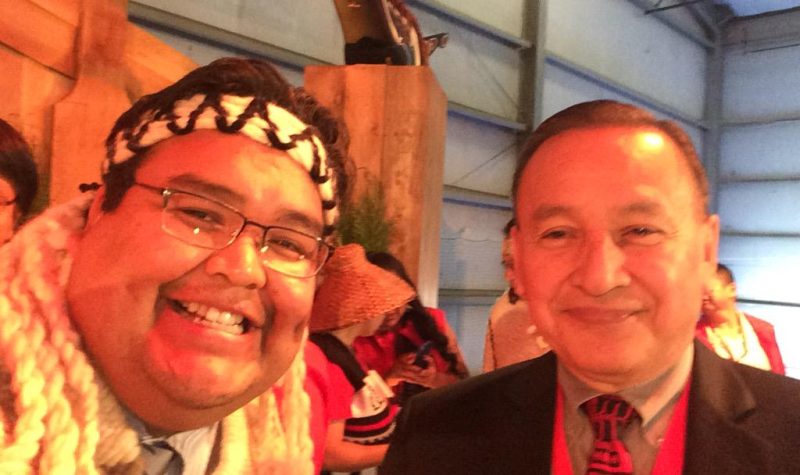

Chief Don Tom, of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, just the latest group to raise red flags about health authorities keeping secret information about local cases in highly vulnerable populations.

Not enough information on COVID-19 cases is being provided to organizations serving vulnerable Indigenous people in British Columbia — whether it's in the Downtown Eastside (DTES), where multiple cases have recently been alleged but not confirmed by authorities, or in more First Nations in more remote areas of the province.

Knowing the local risks and dangers — and possibility for a potentially deadly outbreak — is a key aspect of what some are calling Indigenous "data sovereignty," said Chief Don Tom, vice-president of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs which is based in the DTES and represents many nations in all areas of the province.

Several cases of COVID-19 have emerged, for instance at least two staff at First United Church, which has stopped taking new shelter residents as a result, and previously at a Salvation Army homeless facility. Others have reported residents and frontline staff testing positive and scaling back operations, and several low-income single resident occupancy (SRO) hotels in the area have posted warnings of cases among residents.

"Shelters and other places have expressed concern regarding some positive cases, and I think around the criteria of what is considered an 'outbreak,'" Tom told The Pulse on CFRO. "With a vulnerable population like the DTES, they are sometimes forgotten.

"We must make sure Indigenous and non-Indigenous people there must have access to safe housing and a testing facility," Tom said.

Tom said there's a link between the disproportionately Indigenous DTES neighbourhood, and a new lawsuit by three First Nations in other parts of the province, which say it's problematic that health authorities refuse to provide local outbreak data at any level below major cities or large health regions. Authorities say they cannot provide more detailed information on COVID-19 cases because it could violate privacy, or cause stigma against particular communities or neighbourhoods.

With a predicted second wave of the coronavirus expected imminently, Chief Tom – who is also elected leader of Tsartlip First Nation on Vancouver Island — said that rationale for hiding public health data doesn't stand up to scrutiny from at-risk communities.

"Whether you're the DTES or rural First Nations, the reality of catching the virus or having an outbreak in the community is real now," Tom said. "First Nations deserve the opportunity to have the information available so they can make informed decisions …"

"When we have limited information you can't do that effectively … During a world pandemic, information should be shared," he added. "There's been outbreaks of measles before, and that information was shared. So data sovereignty is also in question too."

His concerns echo those of Union Gospel Mission's spokesperson Jeremy Hunka earlier this week, who told The Pulse on CFRO more coronavirus infection data should be provided at very least to the frontline organizations in the most at-risk areas, such as homeless shelters. And although there are coordinating groups sharing resources between homeless-service nonprofits, Hunka has only heard the same rumours as others about unconfirmed COVID-19 cases in other homeless shelters.

It make preparation and prevention more difficult, Hunka noted, even though his and other organizations are working as hard as they can to anticipate any areas of risk.

"People need to know — it's one thing to go online check the BC Centre for Disease Control's website, but it's another if you don't have a phone or Internet, or if you have real reasons to mistrust authorities," Hunka said. "There's a tricky balance for the health authority, they have their protocols and don't usually announce things unless there's an outbreak and it meets those criteria.

"… But in the absence of clear information, it's often very likely that rumours or something else will fill that vacuum; that's often anxiety and fear. Generally, the more information the better, especially if you're talking about a pandemic in an area of vulnerable people. So I'm glad that people are raising those concerns."