In Ontario, the sexual education curriculum taught in schools has been a point of contention for a long time, and a recent report suggests that it hasn’t improved.

Action Canada for Sexual Health Rights, an organization committed to fighting for sexual health rights in the country, released a report this summer that summarized what was discovered at a virtual meeting of sex-ed champions across the country in October 2020. The findings of their meeting was that the state of how sexual health is taught in schools in Canada is “dismal.”

A significant problem is that most students get their sexual education from school instead of other outside resources, such as their families or doctors.

A study conducted in 2018 by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada looked at the catchment area of schools around the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa found that 80 per cent of students identified school as their most significant source of sexual health information.

But the same study found that only one third of educators had been trained properly in teaching the topic.

Action Canada’s report identified that this one-channel delivery of sex education places an unfair burden on teachers, which was further exacerbated by the pandemic.

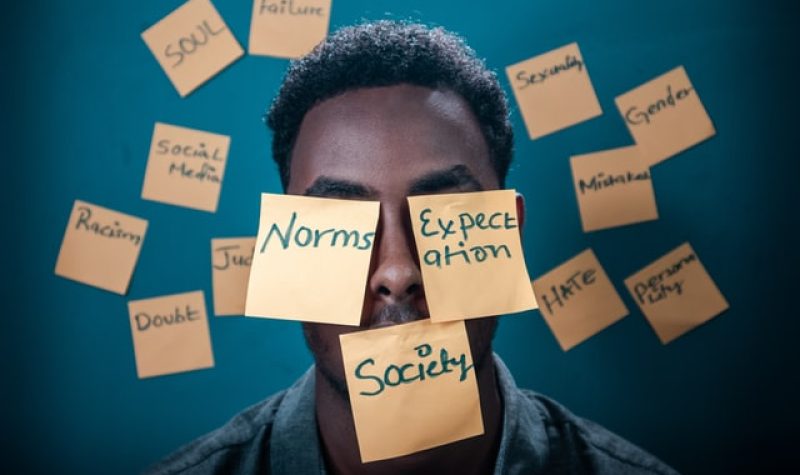

It also identified other issues, such as gatekeeping from parents, not enough direct youth involvement with the curriculum, and no standard set by individual school boards on how to teach sex ed. Additionally, there was no guarantee that students were taught about consent, violence, gender, sexuality or pleasure — the lack of which all enforce attitudes of misogyny, homophobia, transphobia and racism.

Melanie Holjak, a registered public health nurse in the Haldimand-Norfolk region, witnessed firsthand how external support systems for teachers were taken away, when the Ford government made cuts to the public health budget in 2019, reducing the number of public health units from 35 to 10 and reducing provincial funding by more than 20 per cent. This left health units scrambling to find ways to make cuts to the services they provided. At Holjak’s health unit, they eliminated all sexual health services.

This meant that a service normally provided to the school’s from the nurses of her health unit was no longer available.

“Public health nurses were present at the secondary school on a weekly basis,” she said. “Students would be able to book appointments to see a public health nurse to access birth control, [seek treatment] for sexually transmitted infections, and nurses would actually go into the classrooms and deliver components of the sexual health curriculum.”

In addition, nurses helped to shape the curriculum and ran question and answer periods so that students could ask potentially personal questions to someone other than their teacher.

With the pandemic, nurses everywhere were no longer able to go into schools, and health units turned to focus entirely on COVID-19. Holjak is hopeful that services offered by nurse’s might resume. But she can’t be certain what impact the fourth wave will have.

Listen to the interview below with Melanie Holjak, a public health nurse to learn more about what the sex-ed curriculum lost to the COVID-19 pandemic.