Sackville area residents will be asked to weigh in about their experiences in health care on Thursday night at the first of many online consultations to be held in the province over the next two months.

The session takes place on Zoom, starting at 6:30 p.m., and you can find information on how to join at this link.

To help get you thinking about the issues around health care in Sackville and the province, CHMA called up Stéphane Robichaud, the CEO of the New Brunswick Health Council, a government organization created in 2008 to report publicly on the performance of the health system and to engage citizens in the improvement of health service quality.

Hear the full interview with Robichaud here:

One of the recent articles published by the New Brunswick Health Council highlights a disturbing trend in life expectancy for New Brunswickers. After decades of steady increase, life expectancy at birth started to drop in New Brunswick for people born in 2013 and afterwards.

Robichaud says the health council found an increase in “avoidable mortality,” measured as deaths that occur before the age of 75, which is contributing to the decline.

And out of the top 10 causes of avoidable mortality in the province, five are what the council deems “preventable,” or related to things like physical activity and access to healthy food.

Robichaud says it speaks to the need for the province to do, “a much better job at everything pertaining to prevention and health promotion.”

When looking at the broader determinants of health, Robichaud says health services and health service quality are just one, and are estimated to weigh in only about 10 per cent on the health of a population.

Meanwhile, socio-economic factors weigh in at about 40 per cent, and health behaviours at 40 per cent, says Robichaud.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for improvement in the quality of care. The council also identified a decline in New Brunswick’s performance on treatable issues, related to timeliness and quality of care.

“When we last dove into that type of info, New Brunswick was not doing well compared to the rest of the country on the preventable causes, but was doing relatively well on the treatable side,” says Robichaud. “So you know, the life and limb type of situation, if you need urgent care, our system was relatively good.”

But, says Robichaud, the performance on treatable issues has declined over time.

Robichaud says that how primary care is delivered in Canada could play a role in both how we perform on preventable as well as treatable health issues.

“Canada started with two decisions,” says Robichaud. “We pay for everything provided by a doctor, and everything that’s provided within hospital walls. And we’ve essentially evolved around those two elements since the 1960s.”

“In other countries, early on, they’ve acknowledged other professionals,” says Robichaud, such as pharmacists, nurses, and other health practitioners. But in Canada, we remain locked in to family doctors and hospitals.

“Many doctors today will actually speak to the challenge that this poses,” says Robichaud, “because they themselves recognize that some of their patients would be better served if they were in front of maybe a nutritionist or a social worker.”

“So we have to make that step at one point,” says Robichaud, to maximize the variety of roles at work in health care. “It includes better use of nurse practitioners, nurses, other professionals. And it does still include using, in an appropriate and proper fashion, family doctors as well. There are things that they’re better equipped to diagnose than other people, and you would want to make sure that they were present for that.”

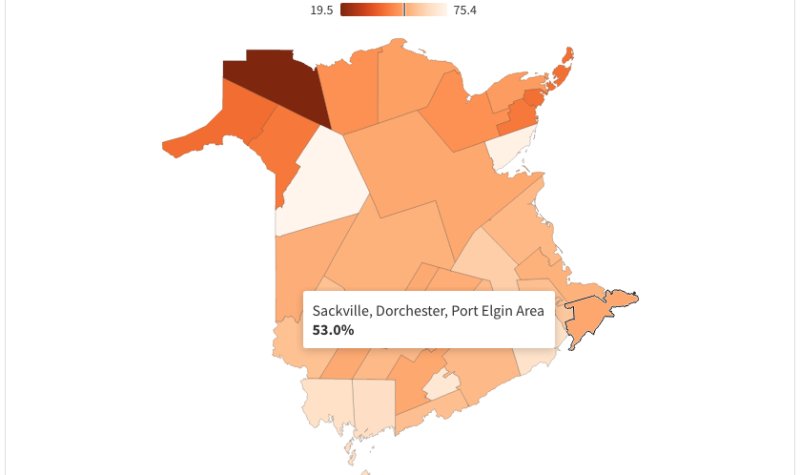

One other finding of the health council is that performance issues in health care are wildly variable throughout the province. The council has put together community-level data to show how people are faring when it comes to certain measurements.

One thing they measured is timely access to a family doctor. Sackville came in about average for New Brunswick, with 53 per cent of people saying they were able to see their doctor within five days. The five day measurement was chosen because most people would forego going to the emergency room or an after hours clinic if they could get an appointment within five days, says Robichaud. Though it’s close to average, Robichaud points out, “it’s not so good for the 47 per cent.”

“If the whole province could be at 75 per cent or more, that would be a good first step,” says Robichaud.

Robichaud says having a family doctor is less of an issue in New Brunswick than timely access to appointments. In Zone 1, 92.7% of people have a family doctor, even though a much smaller percentage (58.6%) says they can see them within five days.

Patient Connect New Brunswick estimates there are between 30,000 and 35,000 New Brunswickers without access to a primary care provider in the province, or about 4-5 per cent of the population.

In the Sackville area, there are 341 people actually registered with Patient Connect, waiting for a family doctor. That’s just over 6 per cent of the 2016 census population.

Strangely, the council found that having a higher concentration of doctors in a health zone does not necessarily result in better access.

Robichaud says his advice for Sackvillians participating in health consultations is to share their experience, and also be open to hearing about other experiences.

“It’s a key opportunity for citizens to hear perhaps stuff that they may not hear otherwise, which is good,” says Robichaud. “And also to relay what they have on their minds.”

Robichaud says he’d like to see changes in how communities are engaged around healthcare.

“Our health system does not understand the needs of its communities very well,” says Robichaud. “It’s not something it’s done very well for the past 60 years.”

“As a system, we have to get better at making this more of an ongoing conversation between the community and our health service organizations.”

You can find out how to participate in the consultation sessions this Thursday, March 4, at 6:30 p.m., right here.