By Tara Warkentin

One in every three bites of food we eat depends on bees. Without bees, our local and global food systems would collapse. Recently, Colony Collapse Disorder has become a buzzword. It refers to the sudden death of honeybee colonies from a myriad of causes, from toxic pesticides to viruses, to disease, and is becoming more and more common in industrial beekeeping operations. But, could the Colony Collapse plague Cortes Island’s own bees?

In this episode of Cortes Currents, I set out to learn what threats Cortes Island’s bees face. I speak to Sharon Figueira, an aspiring beekeeper, about the most ethical way of getting bees on Cortes. I seek out the advice of Tony Clark, to hear what he’s learned in his twenty-plus years of beekeeping on the island. We also delve deep into the world of fungi with Paul Stamets and find a surprising source of hope for our bees. Tony Clark, to hear what he’s learned in his twenty-plus years of beekeeping on the island.

#1 – Learn

Learn as much as you can from books, local beekeepers, and by observing the bees themselves.

“There are so many bee species… they’re all so beautiful,” Sharon Figueira tells me, as we watch wild bees and honeybees forage on her blueberry bushes. I’ve come to find out what it takes to become a beekeeper on Cortes. Sharon hasn’t got bees yet, but she’s hoping to catch a swarm. A swarm is when part of a colony flies away from their old home, in search of a new one. In our climate, honeybee swarms rarely survive in the wild. But other beekeepers can catch the swarms, and house them.

Sharon has hoisted a hive high into the air, and faced it to the south, as she’s been instructed by beekeeping books. She’s also built small swarm traps–wooden boxes with a small hole in the front, to try and attract bees to her garden.

When I ask Sharon why she has chosen to catch a swarm, rather than just order bees from one of the numerous online retailers, she says she doesn’t want to bring mites or viruses to the island, because they could infect all the island’s colonies, and lead to a Cortes-wide colony collapse. She tells me it could be “disastrous for all the beekeepers on the island and the bees.” Sharon says if she’s not able to catch a swarm, she’ll try and buy bees from another Cortes beekeeper.

#2 – Get Local Bees

Get bees locally. Talk to local beekeepers, and see if they are willing to mentor you or sell you bees.

Sharon walks me to her gate. Everything’s pretty overgrown on the margins of her garden, and she explains that it isn’t a mistake. “When I arrived here from Vancouver,” she tells me, “I cut all the dandelions.” But, she noticed that when she forgot to mow her yard, there was an audible hmmm in the air. She realized the dandelions were supporting the pollinators that visited her garden. … “I think you have to change your approach,” Sharon says. “If something is supporting the bees, it’s not a weed.” In fact, research from SFU’s Pollination Lab has found that native plants are especially important for wild bees’ survival. On Cortes, pollinators can’t rely on enormous, industrial fields and orchards for food. While this is an advantage when it comes to harmful toxic exposure, it means they depend on wild plants to build up their honey stores and survive the cold winter.

“Cortes’ main honey flow comes from the blackberries,” Tony Clark tells me. He’s been keeping bees on Cortes for decades, so he knows what happens when there aren’t enough blackberries. A few years ago, when road crews cut back the blackberries across the island in one day, beekeepers had empty hives and had to feed their bees sugar water so that they would survive the winter.

Other important wild food sources for bees on the island are huckleberries, salmonberries, maple flowers, foxgloves, elderberry, and salal. Cortes gardens don’t provide bees with enough food to survive, let alone produce honey. Plants on the margins of gardens and roads can support pollinator survival, and ensure successful gardens for us.

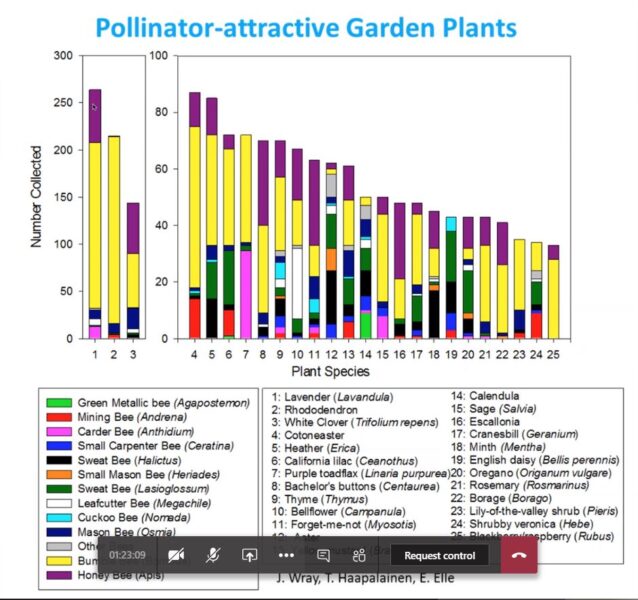

Elizabeth Elle’s research surveyed the most popular native and garden plants for pollinators in Vancouver. Image source: Elizabeth Elle, SFU Pollination Lab.

Elizabeth Elle’s research surveyed the most popular native and garden plants for pollinators in Vancouver. Image source: Elizabeth Elle, SFU Pollination Lab.

Tony agrees that we can all care for island bees, by changing our gardening practices.

“I think the best thing people can do on Cortes Island to help the bees is… [apply] put those pesticides on [fruit trees and garden plants] in the evening.” Tony says. “At that time, the bees are all at home, and then by the time the morning comes [and the bees are foraging for food], the pesticides have kind of done their thing… our bees aren’t going to get poisoned.”

Still, research shows that even the most careful pesticide application can harm bees. Many common “pest control” products marketed at both home gardeners and the agriculture industry contain a type of pesticide called neonicotinoids. The toxic compounds in neonics, as they are commonly known, persist long after pesticide application. Seeds in garden centers and commercial agriculture alike are treated with neonicotinoids, and months later, when the flower blooms and bees forage on pollen, bee fatalities rise. Neonics poison bees, and make them more vulnerable to other threats, such as viruses, mites, and extreme temperatures. Despite a ban in Europe, the outcry of hundreds of scientists, and hundreds of peer-reviewed articles confirming the deadly effects of neonicotinoids on bee species, they are still are allowed in Canada.

#3 – Don’t Use Toxic Pesticides

Don’t use toxic pesticides on your lawn and garden.

A honeybee with 2 Varroa mites attached to it’s back. Varroa mites live parasitically by feeding on the honeybee’s fat stores. Image source: Krishna Ramanujan, Cornell University

In addition to pesticides, varroa mites threaten bees’ survival. Most beekeepers, including Tony, routinely medicate their bees against mites and the viruses they carry. Paul Stamets, mycologist and beekeeper, has found a novel treatment option using mycelium. Listen to Stamets explain his bee feeder in the video below.

Stamets with a Red Reishi fungi, one of the species that has been found to give bees resistance to viruses.

Keeping bees is not just about honey. Its also about connecting with a community of other beekeepers, to ensure the collective survival of Cortes Island’s bees. Tony urges island beekeepers to communicate because a sick bee in one hive can fly up to five miles away, infecting other colonies. With Cortes’ small landmass, it wouldn’t take long for the infection to spread to all the island’s hives. But, there is an advantage to Cortes’ small size: the correspondingly small number of beekeepers can work together, coordinate treatment efforts, and share knowledge. It’s not just bees that keep our food system going, but also, mentorships. connection. Each of us, sharing what we know, so that all of us can be healthy. It’s what the bees do, for the health of the collective colony.

So that’s the fourth and final lesson I’ve learned from the bees and their keepers:

#4 – Share What You Know

Share what you know, so that the whole community can be healthy.

I’ve been learning about bees at Quest University Canada. I collaborated with my peers to make an educational, science-based website, which you can find here: https://thelittlestbeebook.wixsite.com/website

We have also made a printable bee book, which you can download on our website

Many thanks to Sharon Figueira, Tony Clark, Dr. Colin Bates, and my peers at Quest University Canada, for the time and knowledge that informed this story.