By Max Thaysen

Tactical teams with assault- and sniper-rifles dropped out of black helicopters. Specially trained military-style police demonstrated snowmobile stunt skills. Indigenous heroes sang songs of love and consequences on a Mad-Max battle-bus. There appeared to be directors and cinematographers. It was a high-budget production. I had a front-row seat and played the role of Legal Observer.

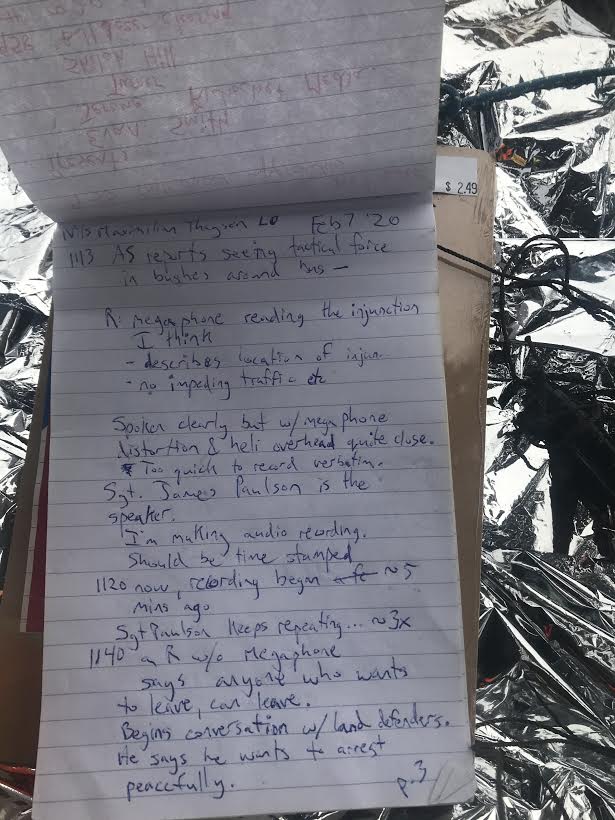

On the morning of Friday, February 7th, the RCMP moved in to raid the second of four camps along the gravel road that passes through the Wet’suwet’en Nation, Gidimt’en Territory. The RCMP were enforcing a court injunction that prohibited anyone from blocking access to anyone working on the Coastal GasLink pipeline. I was a legal observer for that raid – a collector of information for the purposes of legal defense.

ACT 1

I spent three days at the camp known as ’44’ – all the camps are named for their distance from Houston, BC along the Morice River forest service road. 44 was the site of the main conflict with RCMP in January 2019, over the same issue.

The Unist’ot’en Healing Centre is at 66, on the far side of the bridge over the Wedzin Kwah (aka the Morice River). This year, there are camps at 27, and 39 as well – not for blocking access, but for handling supplies, housing Wet’suwet’en people and their supporters, hosting media, and tracking the movements of RCMP. 27 is just before the police checkpoint that controls access to the road into Wet’suwet’en Territory. 39 is behind the RCMP checkpoint, at the start of the indigenous blockade. And there’s the blockade: 5 kilometers of fallen trees, tire piles, a metal gate and a wooden wall on a bridge and behind that, a battle-bus with a tower on it.

Thursday morning the crew at 44 was aroused before 5am by reports from from 27 on the inter-camp 2-way radio:

“Police passing by now, in formation… I’ll count the vehicles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.”

A few minutes later, reports from inside a communications station in a truck at 39:

“Police have breached the camp. They’re coming in the tents.”

“First arrest made!”

“More arrests!”

“They’re putting tape on the windows of the [communications] truck. Probably to smash the window.”

“They’ve smashed the window”

“Aiy-yi-yiy-yiy-yiy-yi-yiy-yi”, the operator cries out bravely.

Radio silence.

Back at 44, the land-defenders knew that they were next and there wasn’t much time. Reports came in from 27 that 20 more RCMP SUVs had blasted up the road for the next push.

Police spent the rest of the day clearing the road of various obstacles. Trees and tires had been put in their path to create a buffer of safety between folks on the land and the ‘rule of law’. By 3pm machinery could be heard around the corner from a barricaded bridge in front of camp 44.

Everyone was ready. But this wasn’t the moment. It was too late in the day for the RCMP to take on the bigger, more established, more fortified 44.

Some suspected they might wait for darkness. Some thought pre-dawn was likely. The thinking was that this battle is taking place on a few different levels – on the ground, with bodies and assault rifles – and in the media, the battle for the hearts and minds of ‘Canadians’. And video doesn’t tell its story as well in the dark.

Legal Observer

The raid at 39 was swift and strong. We heard reports that people were told they couldn’t film police. We heard guns had been drawn.

There were no legal observers there. There have been many people volunteering to perform the service, but generally only during daylight hours.

Legal observers record statements that police make, names of arresting officers and their arrestees, ask questions to clarify communications, and they watch for inappropriate behaviour.

Just having a legal observer on the scene can go a long ways toward ensuring that there is no inappropriate behaviour. Most people behave better when they’re being watched.

ACT 2

As darkness settled in at 44, the defenders began to relax a little with reports of the police convoy having passed by 27 again, on their way out. Would the raid come in the morning? Would there be a day of rest?

I began to reflect on something I heard from journalist Jerome Turner, who was also staying at 44. He said that his editor was worried and reached out to the RCMP to see what kind of risk he was in. The answer was that everyone at 44 would be arrested, even the media.

I realized that my ability to record the details of the event would be compromised early on, as I was likely to be arrested first…. I considered my options.

The land defenders had made a three-storey tower from chainsaw-milled logs on top of a converted school bus. There they would make their stand, the tower keeping them at a distance from the police forces. Perhaps I could join them and I too would have more time to observe. But this would put me too close, make me a violator of the injunction, and injure the tragic beauty of the scene.

Legal observers are meant to be at the edge of a situation – close enough to watch, but not interfere or participate. Plus, my uniform, a white hardhat and a high-vis vest, would be an aesthetic clash.

Then it occurred to me to climb a tree. I could use the advantage of height and challenging access to create time and space between me and the consequences of being on the scene.

So at around 11pm, I began gathering supplies. I found a bucket for bathroom breaks, a bin of climbing equipment, and a hatchet to limb the tree for visibility and to close the trail behind me.

I selected a tree 30 feet from the centre of the road, perpendicular to the bus-tower. I set to work clearing most of the lower limbs, leaving only small weak ones that I could reach down and remove from above. I cleared some branches at a height of thirty feet so that I could see 180 degrees, the whole scene of the raid. I strung my safety lines and 2×8 board for a seat. And at 4:30 AM I was ready to catch a few hours of sleep.

As I lay my head down for what I figured would be a short rest, I pondered… what was I doing here. In many ways, I didn’t know…

When I take the the time to reflect on where humanity is at, what kind of relationship we have with our little blue planet, and what kind of future we might be bringing to bear… I get lost and overwhelmed.

Going to visit a place and a people like Wet’suwet’en brings relief: here are a people who belong to each other and to the land. Here are a people with a clear vision and a righteous foundation that extends as far as the mind can see into the past. And I can visit and support their mission.

The Hereditary Chiefs of the five clans of the Wet’suwet’en Nation have full jurisdiction under their law to control access to their lands. They have directed Wet’suwet’en people and their allies to evict Coastal Gaslink, who never had consent to begin with. The camps are there to enforce that eviction and to demand that the rights and title of the Wet’suwet’en be respected.

Revolution flows like water – it gathers in the cracks and low places, rushing where it gathers enough mass.

Lending A Hand

Mostly visitors are asked to come and lend a hand with camp duties. There is always food to prepare, firewood to gather, snow to shovel, water to carry and construction projects.

I had just finished a day of firewood at 27 when Molly Wickham, a leader in the Gidimt’en clan, asked me if I would be willing to assume Medic duty at 44. She said her medic there had to leave and she wanted someone with some medical training there in case any of her people needed treatment.

I said no at first, fearfully, thinking of my sweet, precious life back home. I knew that the raid was coming soon. RCMP forces had been amassing for a week in the nearby towns. I didn’t know when I might be able to make it out of the territory, or when I might be able to make it out of jail; I didn’t know what kind of a record I could get for being on the scene of such a high-profile conflict, and at the back of my mind, was the risk of bullets flying.

I was torn. I am extremely fortunate to have a beautiful life – but to save that while standing in front of a brave leader who is trying to save her land and her people’s way of life… I felt small. But to be a small part of such a bold and important effort – that, is a life. And I would have been crazy not to accept the opportunity to give of myself in that way.

I also considered something that ‘Green’ told me at Unist’ot’en Camp (66) on a previous trip in December. Everyone had been talking about the upcoming raid and who was going to stay and who had to go and who was ‘arrestable’. I had to go and I didn’t feel arrestable. Green, an indigenous Dene man, while respecting my decision, gently let me know that they needed settlers to stand with them, they needed white people to stand with them – it keeps indigenous people safe. He had already told me many horror stories about how his people were being treated by the RCMP where he is from. That responsibility sat heavy in my chest as I walked away.

I Changed My Mind

I changed my mind in a brief moment and accepted the mission.

ACT 3

The radio woke me up at 7:30: “RCMP convoy passing 27”. I took my position in the tree and the land defenders took theirs: one on the third storey of the tower, one on the second, and two on the ground, prepared to seek refuge in the bus and two locking themselves into a cabin back away from the road, out of sight.

Just four humans stood before the RCMP clearing the road. They were there on orders of Chief Woos of the Gitimt’en Clan of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, one of them was Chief Woos’ daughter. Those four had uncountable others supporting them from around the world. Those four called on their ancestors to be with them.

A song began from the tower, a song from the Gitxan Nation that is meant to gather the clans. The Gitxan Nation has long been allied with the Wet’suwet’en. They have joined together for many battles. The man at the top of the tower, singing, is Gitxan.

By 9:30 a bulldozer crept around the corner followed by a group of 20 officers. As the officers slowly made their way to the bridge and its barriers, both a metal gate and a wood wall, the helicopters could be heard approaching.

The commanding voice of Sergeant James Paulson began from a megaphone, while the helicopters roared right overhead, at times drowning him out. He read out the injunction. The sounds of war filled the air.

When the legal reading was complete, a kind-sounding man began offering to the defenders that they could leave without arrest if they wanted to. Helicopters circling overhead made him largely inaudible, and requests for him to use the megaphone were ignored.

The offer was declined. And the tower made an offering of their own – a warrior song.

The helicopters were dropping teams of tactical police with military-style uniforms and equipment in behind the barricades.

Jerome Turner, the journalist, later told me that the tactical team, called the RCMP Emergency Response Team (ERT), pointed their assault rifles at him as soon as they hopped out of the chopper. Denzel Sutherland-Wilson also reported, from the top tier of the tower, that there were sniper rifles pointed at him.

The police began moving in from the rear, probably fifty officers, reaching the two media people first: Jerome and a filmmaker named Kit. I couldn’t hear what was being said, so I called out, “Hi, I’m the legal observer and I need to hear what you’re saying too, please.”

No response.

I hollered to Mackenzie, “What are they saying to you?”

Mackenzie said that he was told he was in violation of the injunction for being in the exclusion zone.

I asked the police, “Why is the media being told to leave? Who’s in charge here?”

No response.

One officer had a fur-hat on, and seemed to be giving orders . As he passed by me with other officers in tow, he said, “don’t deal with that guy”.

I repeated my request to know who was in charge and why the media was told to leave.

No response.

The RCMP put the two media guys in a secluded zone 60 ft away from the land-defenders, and they were allowed to film. Two ERT members were assigned to watch me. A police dog and handler began scouring the area for any threats to RCMP safety around the road and under the bus – they found none.

The boss in the fur hat continued placing officers around the bus, setting the stage. There were about 30 officers nearby, including a half dozen ERTs. Among them were five officers with video cameras, spread out, capturing the happenings. One camera and two ERT officers were trained on me – watching for any trouble from the legal observer.

The fur hat placed a dog and its handler at the front of the bus, saying “you look good here.”

I continued to shout out questions regularly. Eventually an officer near me relented and gave me the field commander’s name and title – Staff Sergeant Dickinson.

I was filming constantly and taking notes on everything that I saw.

Men in high-vis vests examined the gate on the bridge and proceeded to cut it down with torches. Then the chainsaws came out and cut through the wooden wall. The excavator approached and lifted both off to the side. The bridge was cleared.

Denzel requested that the snipers stop pointing their guns at him. Dickinson said that wouldn’t happen. He asked some other officers from the Division Liaison Team to help get those snipers to stand down. After initially refusing, they agreed to look into it.

I saw gaggles of RCMP members wandering about, who looked as though they hadn’t been out in the field in a while, probably lawyers, strategists and higher-ups. I thought about how the RCMP had identified social-media-savvy indigenous people as a top-priority threat.

The tower had a 2-way radio and a WiFi connection. They were getting reports from 66, 27, the cabin. They were reporting on Facebook. The people in the cabin were being told they were under arrest, but the RCMP couldn’t get into the cabin.

Finally Staff Sergeant Dickinson responded to a couple of my questions. He said ‘Atfield’ was in charge and that he didn’t know what charges were being laid on the people in the cabin. He asked how I was doing, if I was warm and secure, “you’re not going to fall are you?”

Enter The Snowmobile Team

Enter the snowmobile team, stage left, the comic relief. ERT members dressed in tactical brown uniforms rode shiny high-performance snowmobiles across the creek next to the bridge. They then began circling off the road and popping back up on to it over and over. I thought they were showing off because each time they came up the bank the front-end would take some air. It became clear, though, that they were making paths that people could walk on, without which anyone would sink into the soft snow up to their waist.

Next an ERT member tried to fire up a land-defender’s snowmobile parked at the bottom of the tower.

“It’s not going to start for you!” Denzel said.

“This is the only time I’ve considered getting down from this tower – to show you how to start that [machine]!”

The ERT officer, frustrated and embarrassed, pulled the drive belt off and towed the snowmobile away.

Removing Indigenous Peoples

With the scene secured and everyone in their places, the RCMP began the removal of indigenous peoples from their land.

They started with the two in the bus. They were given the option to leave without arrest – they said they weren’t leaving. I couldn’t see or hear the far side of the bus where that action was happening, but moments later the two were being led away in handcuffs, quietly.

Next the RCMP turned to the two in the tower. They tried to entice the land-defenders down, preferring not to have to go up there to get them. An RCMP officer read them the court injunction and told them to gather their belongings and leave or they would be arrested for contempt of court, in violation of the injunction. They explained that it was dangerous to be arrested up in the air and that it would be safer to just come down on their own – that way, no one would get hurt.

The defenders responded by explaining that the RCMP were trespassing on Wet’suwet’en Territory and that there was a another option: the RCMP could leave and that would be the safest option.

The defender from the second tier climber up to join the third tier.

Three ERT members were then assigned the task of climbing the tower and bringing the two defenders down. They methodically set up three ladders. Two went up, harnessed and roped in, and one stayed on the ground managing the rope that would catch them if they fell.

The tower was about 35 feet tall. It had four legs that straddled the bus and extended to the second floor. A pole that sat on the roof of the bus extended up through the second floor and supported the top tier – a small 4 foot by 4 foot platform with no railings.

The climbing ERTs continued to try to build a relationship with the fortified land defenders. They wanted to know if the land-defenders were going to make any sudden moves or try to resist the officers coming to strap them in and lower them down.

I couldn’t hear all of their conversations. But I think the ERT members were satisfied that no one would make any moves that could be interpreted as trying to hurt someone. Things were moving slowly and things were tense.

I asked the lead ERT officer if there was an emergency medical plan should anyone fall from that height. I was still, after all, the medic for camp 44 and I had my equipment at the base of the tree. My question went unanswered, but moments later an ambulance was pulled up to the bridge within a reasonable response distance.

The ERT members and the land defenders were from different universes. Hearing them talk to each other was like an alien encounter. Each tried to convince the other that their actions weren’t necessary, that they could just walk away. Each seemed unmoved.

With some renegotiation of the ladders, the lead ERT officer moved to the top. And with minimal cooperation from the top-tier defenders, he slipped a harness on one and then the other and each walked down the series of ladders.

The defenders had done what they could to delay and deter the RCMP from removing them. They had built a beautiful stage from which to sing to the land, to sing to their supporters and to sing to their enemies. But further resistance would not have served them – it would likely have resulted in injury and increased legal penalty. And so, in the end, they went without a kick or a scream.

Taking Media & Observers Away

Once all the land defenders had been arrested, the media guys were told they had to leave the scene and were escorted away. If they weren’t willing to leave then, they would have been arrested.

Then the RCMP turned to me. The leader of the ERT asked if I was going to come down willingly. I said that I would, but that it would be nice to have some help. I had cut all the branches that I used to climb up into the tree and I didn’t quite have the skills or equipment to lower myself down safely.

The climbing team from the tower was willing to assist me. At first they said they were going to toss me some equipment that would allow them to drop me in a controlled fashion. But when I didn’t know the names of the some of the knots they wanted to use, even though I had been using them, they decided it would be better to come up and set an anchor for me and use that to lower me down.

I packed up my station while an ERT set up a ladder and climbed into the tree with me. We had some time so I asked him about his gear, and whether he liked his job. Cautiously he said that he did. He told me that he was specially trained in climbing and winter survival.

Once safely on the ground I was told that I would have to leave or I would be arrested. I said that I still had some legal observing to do at the cabin, where there were still two people locked inside. That wasn’t an option for the officer directing me, he said, because of ‘public safety’. Despite feeling that this was a violation of my rights, I agreed to leave and was escorted around the bridge.

I didn’t have any transportation options of my own and didn’t really feel like walking the 44 kilometers to the nearest town. The RCMP had a solution though: they would put me in the paddy wagon with the defenders from the tower.

And so I rode back to the civilized world with the heroes of the day – those who stood 35 feet tall in front of the whole world and sang hope into the hearts of millions who dream of indigenous sovereignty and the end of colonization, a true reconciliation, clean water and air and a resurgence of cultures that are born of the land and survive to this day despite hundreds of years of genocide by Canada.

My Opinion

As a legal observer, I report that I saw members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police being polite and following the procedures of their law to the best of their knowledge. They were slow and careful and had all appropriate medical personnel on stand-by. They gave everyone advanced knowledge of what they were doing and why and they gave the defenders opportunity to respond.

I also felt that my position was ignored many times and that I was unlawfully ordered to leave an area and threatened with unjust arrest.

As a tax-payer, I could not help but wonder, repeatedly, just how much this whole show cost.

As a citizen of Canada, I believe that what I witnessed on February 7, 2020 was a re-invasion of Wet’suwet’en Territory by the Canadian Government. There is no treaty that signs those lands over from Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief authority to the Government of Canada, but that’s an inconvenient little detail that the elected representatives governing this nation would rather not talk about. I believe I saw multiple violations of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, recently adopted by British Columbia and promised to be adopted by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

This program was funded by a grant from the Community Radio Fund of Canada and the Government of Canada’s Local Journalism Initiative.

Special Thanks to Denzel Sutherland-Wilson for sharing his songs, Mackenzie knight for sharing some audio recordings, and Jerome Turner for sharing a pic.