A team of seven scientists lead by the director of the Canadian Ice Core Lab spent 26 days in May drilling 327 metres of ice core from Mount Logan's summit plateau.

It's the largest non-polar ice field in the world, and drilling into the ancient ice will “give us a backward looking perspective so we can look forward," said Alison Criscitiello, the director of the lab.

Most ice this old comes from the poles, so it's unique to have a good sample from the North Pacific.

The first phase of the expedition was to slowly ski the 5,200 metres to the plateau, to acclimatize to the elevation, said Criscitiello. The second was to set up the 900 pound drill, flown in three separate helicopter trips, and a camp on the 20 kilometre plateau.

Also along for the expedition was a team of three filmmakers—a sound person, a visual person and a helper. Greg Hill was the helper. The Revelstoke resident of 20 years had done projects with the film crew before.

"There’s a really cheesy quote that I’ve heard at some point, 'Strange invitations to travel might be dance lessons from God,'" said Hill.

Greg Hill is an adventurer from Revelstoke. Here, he is on the side of Mount Logan. Photo by Alison Criscitiello.

"Super cheesy but the truth is you kind of got to be open to things."

He got the call in April and two weeks later he was taking off from the shore of Kluane Lake in Silver City, Yukon to the base of Canada's largest, tallest mountain.

Mount Logan looms in the St. Elias Range at 5,959 metres. It's the second largest in North America after Mount Denali, nearby in Alaska, in the same mountain range.

Mount Logan in Yukon is the highest mountain of Canada. It's part of the Saint Elias Range. Photo by Leo Hoorn

The expedition was documented by a film crew with the National Geographic Society.

"I think for most of my life so far I kind of ping-ponged between my two loves, cryospheric science and cryospheric exploring," Criscitiello said with a laugh, over the phone from the ice core lab in Edmonton.

In grad school she would work in Antarctica, go to an ice core lab, then write a bunch of papers, then take off for four months to the Himalayas.

Leading a team at the Canadian Ice Core lab means she's integrating her loves with projects like this one—climbing Canada's largest mountain, for a third time, but now with a team of scientists with the intent to stay at high altitude long enough to drill through the world's largest non-polar ice field.

National Geographic supported the trip as part of its Perpetual Planet Initiative, which is supported by Rolex. That’s according to an email from Criscitiello's contact with National Geographic.

On the second day of the expedition the drill mechanic was up outside his tent in the minus 20 degree weather sick with vomiting and diarrhea. Right away they started talking about pulling the pin, Hill said. But the mechanic took it slow, and kept going.

The expedition team climbs to Camp 1 on Mt. Logan. It took them ten days to climb to the summit plateau. Photo by Leo Hoorn.

They made it up to the summit plateau in 10 days.

At 5,200 metres, they didn't have much of an appetite and it was hard to sleep.

"I personally lost 15 pounds, most of us lost about 10 per cent of our body weight just surviving, so there was a ton of things on the line," Hill said.

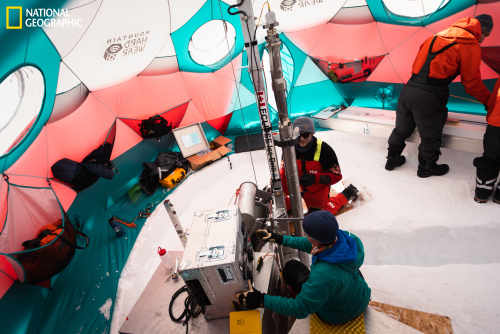

They flew up a huge dome tent to house the drill. They drilled in shifts, 14 hours a day for 11 days, no matter the weather.

The ice core drill in action at high camp. Photo by Leo Hoorn.

"Which is a lot," Criscitiello said, "and it’s a really long time to stay up there at that kind of altitude, I’ve never done such an experiment on myself, staying you know around 18,000 feet for almost two weeks."

Right away one of the scientists got high altitude pulmonary edema, Hill said. He struggled to breath and they had to give him steroids. Eventually a helicopter flew up and hovered above the plateau, and someone threw a 150 foot line down to Hill. He attached the sick man and they flew him off the mountain.

In the end, three from the team of scientists had to be flown off Mount Logan. Hill joined the drill team, because he didn't have much to do, and to make it more efficient.

Using a radar they predicted the bedrock was 250 metres under the ice, but after pulling up 327 metres of core they still hadn't hit the bottom, and they'd used everything on hand to wrap up the samples, flying out the last few metres of ice still stored in the drill.

Criscitiello thought they might acclimatize to the altitude after a few weeks, but they didn't.

"It was just really incredible to watch, basically, these amazing people suffer all for a unified cause," she said.

The reward is the ice core.

It's good, clear core, Hill said. "They’re going to get a really incredible snapshot on the environment and what the climate was doing all in North America during that period, so it’ll be really neat."

Analyzing a core sample taken from Mt. Logan's summit plateau ice cap. The team drilled 327 metres of this core, which they will study for months. Photo by Leo Hoorn.

It's unique to have this ice record to study outside of the polar regions, Criscitiello said.

"There aren’t very many places that over these really long time scales don’t see any melt even in the height of summer ... and have all of the right conditions for these long term records to be laid down in the snow and never melt basically," she said.

"For me, it was the highest risk but potentially highest reward project that I’ve ever dreamed up and pulled off."

These ice cores contain the story of the location from which they're drilled, in this case the gulf of Alaska in the middle of the North Pacific.

The centre of the core samples is "pristine ice," Criscitiello said. "Not only have we not touched it, it hasn’t even seen the air in however many years old it is.”

It will takes months of analysis before they know, but Criscitiello and the other ice core scientists predict it's between 20,000 to 30,000 years pre-Halocene era, which is the geographical era we're in now.

There is a counterintuitive phenomena occurring called elevation dependent warming, where places like Logan's summit plateau are experiencing more rapid increases in temperature over time, than lower elevations. It's happening all over the world, in some places where billions of people rely on the high altitude caches of ice and snow for drinking water.

The ice will be used to study this change, for one.

A stick will go to a lab and used to reconstruct the wildfire history of the area, including what vegetation burned. It will take many scientists months of work to study these samples.

"I can’t even put it into words what it this project means to me," Criscitiello said, "but also to be on this end of it now, having actually pulled it off and to have the ice, it’s about ten metres away from where I’m sitting right now, safely back here."

Listen to a radio story about the expedition by clicking below: