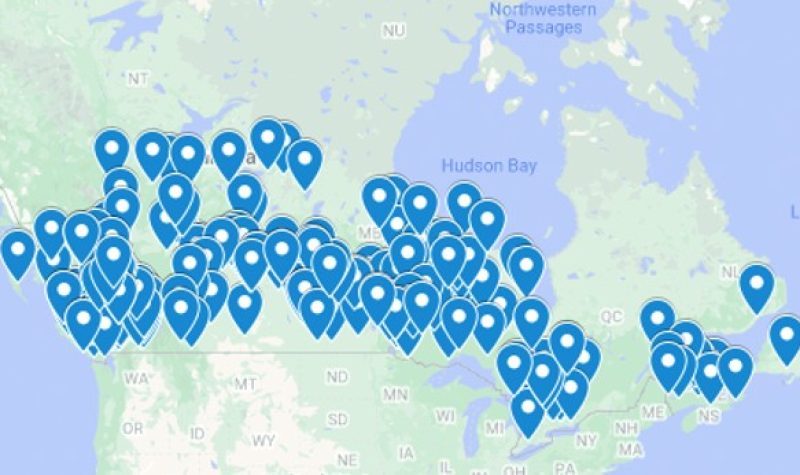

A map of the country is shot through with blue markers, each one pointing to a First Nation that has been affected by a long-term drinking water advisory, meaning that it lasted more than 12 months.

In recent years, the number of communities with unsafe drinking water has dropped, but the long-running problem has remained a source of embarrassment for Canada — and a hazard for residents of the affected communities.

Now, funds from a massive class-action suit are meant to address ongoing problems with drinking water on reserves and compensate people and communities affected, although statutory limits mean that many individuals aren’t eligible. The deadline for claims is coming up on March 7.

More than 250 communities across Canada affected

In December 2021, the federal court and Manitoba’s Court of Queen’s Bench approved the $8-billion settlement between Canada and First Nations affected by drinking water advisories that lasted more than one year.

The class-action settlement applies to boil water, do not consume and do not use advisories.

An interactive map on the website for the class action shows locations across the country known to have long-term drinking water advisories during the time frames covered by the settlement.

In New Brunswick, they include Tobique, Woodstock, Oromocto, Buctouche, Indian Island, Eel Ground, Pabineau and Fort Folly First Nations. Fort Folly, located just outside Sackville, experienced a water advisory between March 6, 2002 and May 24, 2005, according to the website.

The settlement includes $6 billion to deal with ongoing water infrastructure issues on First Nations land, along with $1.8 billion in settlement funds for First Nations and their individual members.

Roughly $1,300-$2,000 per year without safe water

The amount available per person depends on a number of factors, said Jaclyn McNamara, legal counsel with Toronto-based OKT Law.

“The rough amounts are about $1,300 per year for a boil water advisory, $1,650 per year for an order not to consume the water, and about $2,000 per year for a do not use advisory,” she said.

Other factors include the number of people who make claims, the length of time living under an advisory and whether the community is located in a remote location.

First Nations that opt into the settlement can also receive $500,000 and an amount equal to half of damages paid to individual members, McNamara said. People who suffered injuries related to unsafe water can also receive additional compensation.

“There’s no amount of money that can compensate for the harms that people experience living under these kinds of long-term drinking water advisories,” McNamara said. “And those harms are extraordinary.”

“We’ve got a commitment from Canada to make all reasonable efforts to ensure the class members have regular access to safe, clean drinking water in their homes, and have enough of that drinking water to do all the things that Canadians use drinking water for.”

Statutory limits exclude many from settlement

McNamara said about 262 communities that may be eligible had been identified by December.

But the settlement has attracted criticism because a federal statute of limitations means that many people are excluded from the settlement package.

Leaders from an Oji-Cree First Nation in Ontario recently spoke out when they learned the majority of people affected in their remote community wouldn’t qualify, the CBC reported.

Generally speaking, anyone over the age of 26 wouldn’t be eligible, McNamara said.

That’s because there’s a limit on how long adults have to launch legal action following a given incident, but the clock doesn’t start ticking until the age of 18.

“It’s really hard for a lot of people to have suffered under these drinking water advisories and to not be eligible for compensation under this class action,” McNamara said.

Exceptions exist for people with mental or physical conditions that prevented them from coming forward with a claim, she added.

More than 30 communities still under long-term advisories

Thirty-two drinking water advisories lasting more than one year were ongoing in 28 Indigenous communities by December 29, 2022, according to the latest update from the federal government.

One hundred and thirty-seven long-term water advisories have been lifted since November 2015.

McNamara expressed hope that a new sense of urgency about the issue will lead to clean drinking water in all communities. “Hopefully we’ve moved forward on that path,” she said.

Listen to the interview with Jaclyn McNamara of Toronto-based OKT Law recorded on December 13, 2022.