A Mount Allison researcher is going to help contribute some clarity to the confusion over New Brunswick’s mystery neurological disease. Math and computer science professor Matthew Betti wants to survey and study the cluster of cases being investigated as related to a possible new neurological disorder.

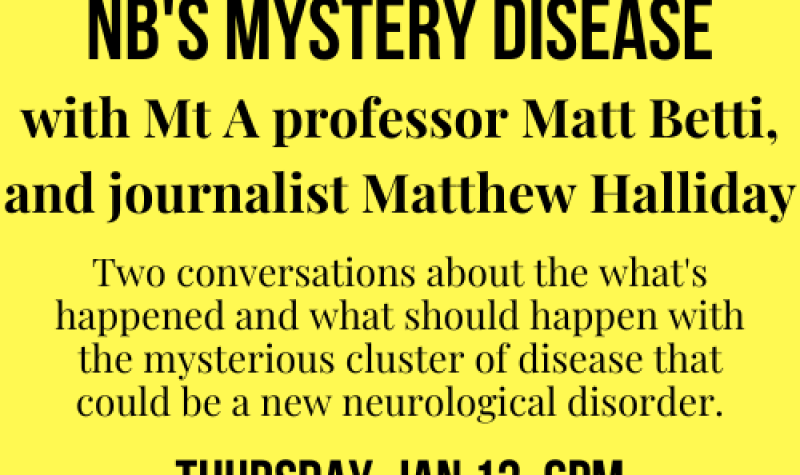

In a recent episode of CHMA Talks, Matt Betti explained the motivation for his study, and how it would differ from the publicly available work done to date by New Brunswick Public Health.

Later in the episode, we spoke with journalist Matthew Halliday about his coverage of New Brunswick’s possible new mystery disease. Hear that episode here:

Betti specializes in infectious disease modelling and has worked for Health Canada throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Betti says the matter of a potential new neurological disorder needs independent study.

“As we’ve seen over the last few years, something as simple as a communicable disease can be highly politicized very easily,” says Betti. “I think it’s important to to make sure that the science is done right, without undue influence of politics, or outside interests.”

“That’s part of the reason why we have this infrastructure that is academia,” says Betti, “to do, ideally, unbiased, independent research, from which you will not see negative consequences from your employer, from government, etc.”

Betti says he’s interested in further exploring the data about the possible new disease, and that the surveying done to date, as published in a report by New Brunswick Public Health, has been preliminary, not extensive enough to draw conclusions about the existence or not of a new disease.

While it did find common exposures among the small group of patients, the greatest of which was lobster, which 31 of 34 respondents had eaten in the previous two years, the New Brunswick Public Health report concludes:

“Based on the findings of this report, there are no specific behaviours, foods, or environmental exposures that can be identified as potential risk factors with regards to the identified cluster of cases with a potential neurological syndrome of unknown cause. As such, residents should feel confident that they are not considered to be at risk of any food or environmental exposures within the province.”

Betti says that finding out a large percentage of people have a certain characteristic is not necessarily significant unless it’s compared with the general incidence of that characteristic.

“If I told you that 60 per cent of people who graduated high school own a dog, you don’t necessarily know whether that’s high. Is it low? Is it average? We don’t know, because we have nothing to compare it to.”

Betti says it’s still early days, but he’s planning a survey that would include control group participants so that such comparisons can be made. And his survey will also cover a longer time period.

“From what I know of neurological diseases, many can lie dormant in your system on the order of decades, not necessarily years,” says Betti. “So I think it’s vitally important to do a survey that stretches very far back in time and that has a very high spatial resolution. It’s one thing to know where the patients are now, but if they were exposed to this five years ago or ten years ago, it’s important to know where they were, as well.”

“The survey that we’re proposing is much more in depth than what is public facing on the New Brunswick survey,” says Betti.

The process is underway to authorize his study, and Betti expects to be able to share results within a year.

Telling the story of a “very strange and unusual cluster”

Journalist Matthew Halliday is one of the reasons why the interest in the possible new disease is what it is today. Halliday published a story in The Walrus Magazine in October 2021 detailing the story of the investigation into New Brunswick’s mysterious neurological phenomenon.

Halliday said when he started out investigating the topic, he was interested simply in the science story: how a group of neurologists and epidemiologists would go about investigating a potential new disease. But things took a turn for him, based on what he found out about how New Brunswick was handling things.

Halliday’s plan was to speak with Dr. Alier Marrero, the lead neurologist looking into the disease, Dr. Neil Cashman, a clinician–scientist in neurology at UBC, as well as the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“I was thinking, 'I’m going to talk to all these people who are getting involved in this and try to really plug into the inner workings of how an investigation like this unfolds,'” says Halliday. “Unfortunately, I sort of hit a wall.”

That wall appeared to be erected by New Brunswick Public Health.

“Every one I tried to reach out to declined to speak, in some cases, suggesting that they were not being allowed to speak,” says Halliday. “One scientist said that they were being 'muzzled' and others were also being muzzled. That was the word they used.”

Finally, Halliday was able to reach a “scientist in the federal public health infrastructure” who opened up anonymously about what was going on.

Halliday found out that there had been a sort of joint investigation underway involving the Public Health Agency of Canada and New Brunswick Public Health, but that was “put on ice” by the province.

Recent reporting by Karissa Donkin of the CBC shows that about 40 subject matter experts started meeting to talk about the disease in February 2021, shortly before Public Health sent its initial memo to health care providers to ask them to watch for incidents of the possible disease. But then by May, after the news of the possible new disease had hit the media, Donkin discovered (via a formal access to information request) that the meetings were stopped at the request of New Brunswick Public Health.

Halliday is careful to point out that his theories on why that decision was made, are just that: theories. But he highlights two patterns at work. First, the mistrust of many New Brunswickers as to the relationship between industry and the provincial government, especially due to the dominance of the Irving family in the province.

“You see a lot of people advancing almost sort-of conspiracy theories around, oh, this company or that company, or this particularly powerful family must be involved, and the government is covering up for them. I don’t really think there’s any evidence for anything like that,” says Halliday.

The other pattern is with provincial government and agencies, which seem to have “the penchant for keeping things in house, keeping things secret, wanting to have a control over the messaging,” says Halliday.

The two patterns no doubt help feed and reinforce each other.

It’s not that Halliday is suggesting New Brunswick Public Health has knowledge of something it wants to cover up, but rather that there could be concern, politically, about what might be investigated and how.

“In all likelihood, public health authorities in New Brunswick probably don’t want federal investigators to come sort of traipsing through the province and testing water and testing food and and finding who knows what,” says Halliday.

One thing Halliday takes time to highlight is the mistaken perception that the Moncton neurologist who first started to flag the possible new disease cluster, neurologist Alier Marrero, is the sole source of alarm and concern over the possibilities here. The province’s website to inform residents about the investigation into the disease states, “Forty-six of the 48 identified cases were referred by a single neurologist and the two other cases were referred by two separate neurologists.”

“It’s often presented as his cluster or something,” says Halliday, “as somehow the product of his thinking alone.”

But though the initial patients were identified by Marrero, patients were then referred to the Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance System in the Public Health Agency of Canada. The senior federal scientist that Halliday spoke to told him the number of people being referred and the kinds of symptoms they were experiencing over such a short time span was unprecedented. Halliday says he was told, “this was a very strange and unusual cluster. There was really no sort of explanation off the top of their heads, that they could think up for this.”

“They, collectively, over a fairly long period of time, looked at these patients, did workups in these patients, did an exhaustive litany of testing on these patients, to really try and figure out what was going on,” says Halliday. “And they were seeking alternate diagnoses.”

“So this cluster was really the product of Dr. Marrero’s thinking, but also the product of thinking from federal scientists and collaborators with the Public Health Agency of Canada,” says Halliday.

New Brunswick Public Health says that a report from an oversight committee made up of six neurologists has been tasked with “ensuring that all clinical due diligence was taken” in work by Marrero and colleagues, and “to rule out any other potential causes or plausible diagnosis.” That report is expected early in 2022.