It’s been 16 years since a UN climate change report highlighted the increasing risk to infrastructure on the Chignecto Isthmus due to rising sea levels, mentioning it alongside the city of New Orleans. But the provinces and the federal government have yet to agree on who will cover the cost to protect that infrastructure. The federal government is promising to cover up to 50% of the cost, but the four Atlantic premiers are calling on the federal government to cover the full cost of the project.

After a recent meeting in Mill River, PEI, the Council of Atlantic Premiers issued a statement acknowledging the isthmus as “a vital corridor at risk due to rising sea levels”, and saying the premiers, “reiterated that the federal government has a constitutional responsibility to maintain links between provinces and fully fund this project.”

A spokesperson for New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs confirmed via email that the premiers were asking for 100% federal funding of the infrastructure project, which was estimated to cost between $190 million and $300 million in a study released last year.

That’s a departure from recent statements by the provincial ministers from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. In an April news release, New Brunswick transportation and infrastructure minister Jeff Carr said, “we want the federal government to be a majority, lion’s-share stakeholder in funding this project, because neither province can afford to foot the bill.”

The release goes on to say “both provinces are pressing for the federal government to carry more than a 50 per cent share of the cost,” but does not go so far as to call for 100% funding.

However, Carr did compare the Isthmus protection project to the Confederation Bridge, noting that the PEI link was “mostly paid for by Ottawa.”

As for the federal government, a spokesperson for Infrastructure Minister and MLA for Beauséjour Dominic Leblanc reaffirmed the invitation for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to apply for federal funding under the Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund. That would allow for a maximum of 50% of the cost to be covered by the federal government.

Local advocates call for fast-action

Two major proponents of the flood protection project say they are focused on making sure the project is completed as soon as possible, and not on the disagreements in who might fund it.

Amherst mayor David Kogon has been aware of the Chignecto flood risk since 2016, shortly after he was elected. He and then-Sackville mayor John Higham helped get the ball rolling on a $700,000 engineering study to look at options to secure the transportation corridor.

Amherst mayor David Kogon and then-Sackville mayor John Higham meet at the closed provincial border in June 2020. Photo: Town of Amherst

Kogon says it’s not his place to weigh in on federal or provincial positions on the issue, but he is concerned about the potential delay that could be cause by a disagreement. “This might be an issue that’s going to take some time to resolve,” says Kogon, “and therefore potentially delay work being done on the dikes. That would be a concern.”

Kogon says he understands the premiers position, considering the widespread impact that a flooding of the CN rail line and TransCanada highway would have. The ramifications go “far beyond the two provinces and affects the entire country,” says Kogon.

On the same weekend that the premiers were meeting in PEI, Kogon hosted a group mayors from Atlantic Canada in Amherst. The Atlantic Mayors Caucus released their own statement calling for immediate action on the Chignecto Isthmus. The group is, “urging the Province of Nova Scotia, Province of New Brunswick, and the Government of Canada to immediately establish a Steering Committee to lead the work required to prepare for upgrade or replacement of the Chignecto Isthmus protective Infrastructure.”

Although they only name the governments of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, the Atlantic Mayors Caucus also says the Isthmus steering committee must include municipal leaders from all four Atlantic Provinces.

Former Cumberland MP Bill Casey is one of the first politicians to voice concern over risks to the Isthmus transportation corridor in light of rising sea levels. He recalls being alerted to a 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which cited the Isthmus corridor as an example of serious risk, along with the city of New Orleans.

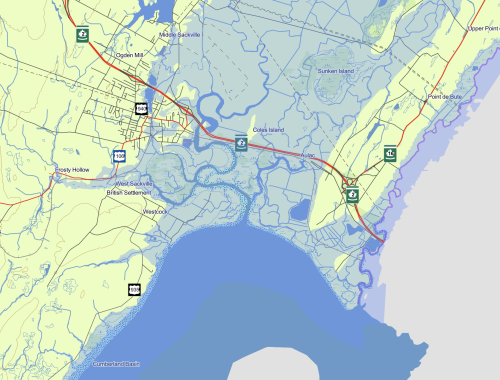

Screencap from New Brunswick Flood Hazard Maps. The light blue area is labelled “Present Day Flood, 1 in 20 year (5% Annual Exceedance Probability)”.

Casey gave a presentation to the recent mayors congress about the Isthmus and the plans to protect it. He says with an estimated $50 million in trade each day traversing the corridor, the price tag of $200 to $300 million to protect it represents just four to six days of a shutdown of the transportation links.

The last funding agreement on the Isthmus problem was agreed to in 2018, when New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the federal government agreed to cost share the engineering study (released publicly in 2022) on how to protect the corridor. The provinces each covered one quarter, with the federal government paying 50% of the $700,000 price tag.

“I think everybody kind of assumed that would be the formula going forward,” says Casey. But now that the future funding formula has come under question, Casey is stressing the importance of fast action. Another Saxby Gale—a tropical cyclone that passed during a perigean spring tide in 1869, washing away the dykes protecting farmland on the Isthmus—could happen again anytime, says Casey. And this time, there will be more at stake.

“The railway is now holding back the Atlantic Ocean,” says Casey, referring to the proximity of the tideline to the rail, especially as it crosses the Tantramar marshes. “It was never designed to do that.”

And behind the rail line there’s the TransCanada Highway, major electrical transmission lines and fibre-optical cables. The impact of a flood will be “total”, says Casey. “As I said to the mayors the other day, if you have a fishery, if you have agriculture, if you universities, if you have tourism, if you have retail, if you have wholesale, if you have healthcare… No matter what you have, it’s going to be affected. Every single thing is going to be affected if the rail line is breached.”

“My main concern is getting started and getting it done. The funding is up to them to decide,” says. Casey. “Whatever the formula is, they’ve got to get at it.”